What is your carbon footprint?

© TIM Garrett 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

What is your carbon footprint?

I would like to make a case that this is the wrong question. In an interconnected world, none of us can be meaningfully separated from the whole, and the whole responds to forces that are external to any of us.

Consider the number of degrees of separation between you and anyone else on the planet. This might seem like a pretty hard thing to assess given how many of us there are and in some pretty far-flung places. I don’t know personally anyone in the Papua New Guinea Highlands (to mention some arbitrarily remote location), but I can be pretty sure that it’s not too much of a stretch to suppose my Australian friend has a friend who has been to the capital Port Moresby where he ran a cross a guy whose cousin occasionally makes trips to the capital to work for “luxury” items to take back to his remote forest dwelling where he presents them to his wife. That would be just five degrees of separation.

So even if relationships are pretty far-flung, it’s like the line from the TV series Breaking Bad, “I know a guy who knows a guy.” None of us is truly independent of anyone else.

The same principle can apply to all of history. Suppose that an estimated 100 billion people have walked the earth in the last 50,000 years. With each successive generation, each of us is related to two others to the power of the number of generations. Exponentials lead to big numbers quickly: 100 billion people equates to just 37 successive generations. So, it shouldn’t take too great a number of generations before the number of your number ancestors is similar to the number of people living at that time. As evidence, all humans look and act pretty much the same. One way or another, there was sufficient intermingling for us all to have ancestors in common.

So, as a first approximation, we are linked through our current activities to everyone alive, and moreover we can be linked by blood to everyone who has ever been alive.

It seems then that the question should be not what is your carbon footprint but instead what is our carbon footprint. We are a collective “super-organism” that has evolved over time by burning carbon based fuels to sustain ourselves and to grow. Individually, we may profoundly feel that we can behave as isolated entities; our personal economic choices, in however limited a way, can reduce the collective rate of CO2 exhalation.

The evidence is against this argument, however. If we term our collective wealth as the accumulation of all past economic production, summing over all of humanity over all of history, then the data reveal a remarkable fact: independent of the year that is considered, collective wealth has had a fixed relationship to added atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Expressed quantitatively, 2.42 +/- 0.02 ppmv CO2 is added every year for every one thousand trillion inflation-adjusted 1990 US dollars of current global wealth.

A useful analogy here is to a growing child, who consumes food and oxygen and exhales carbon dioxide. The rate of CO2 exhalation by the child is determined by the sum of all cellular activity in the child. All the child’s current living cells require energy, and all produce CO2 as a waste product. But here is the key thing: the total number of current cells in the child is not determined by what the child does today, but by child’s past. Over time, the child grew from infancy to its current size, accumulating cells and its capacity to exhale CO2.

For humanity, it is the same. We currently “exhale” CO2 as a total civilization, but our current rate of exhalation is determined by past civilization growth. So, if emissions are so tightly linked to the collective whole, and all past growth of civilization’s consumptive needs has already happened, entirely beyond our current control, what individually can we do right now?

To further illustrate the problem, let’s look at CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. To calculate the actual increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations, one has to consider that the land and oceans absorb a fraction of what is emitted. Estimating carbon sinks is possible but can get pretty tricky. Nonetheless, we can look at the observed relationship between economic activity and atmospheric chemistry to get a sense of what is going on.

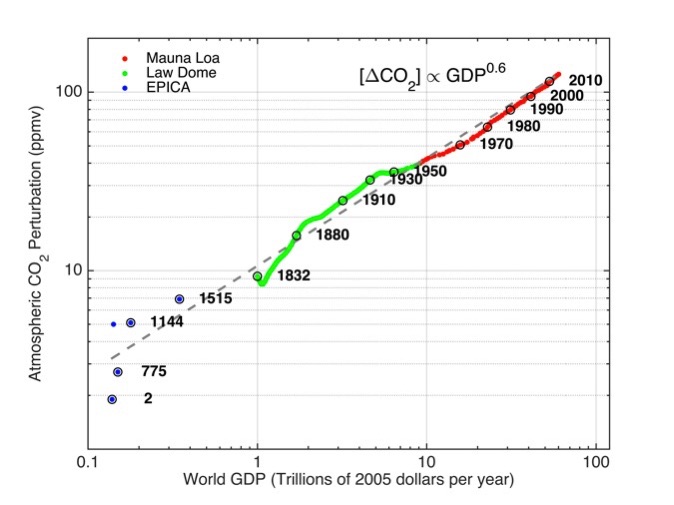

Looking above at the past 2000 years of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, obtained from Mauna Loa in Hawaii and from ice cores in Antarctica, and measured as a perturbation from a baseline “pre-industrial” concentration of 275 ppmv, there is a surprisingly tight power-law relationship with global GDP. For the entire dataset :

log[CO2(ppmv perturbation)] = 0.6 x log[GDP(2005 USD)]

Amazingly, for over 2000 years, the relationship between CO2 and economic activity has been pretty much a mathematical constant.

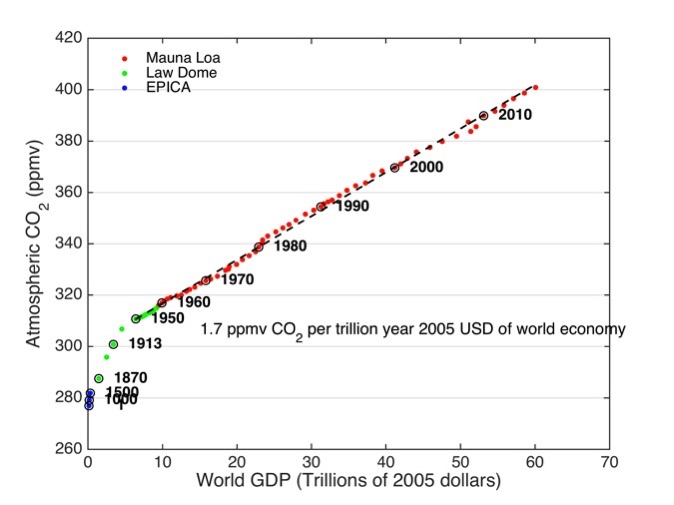

Actually, if we look just at the past 60 years in the above, the relationship is linear and even tighter: since 1950, for every trillion inflation-adjusted year 2005 USD of global economy, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has been 1.7 ppmv higher.

In fact, we could turn this around. With an extremely high degree of accuracy, we could estimate the global GDP simply with a CO2 probe at Mauna Loa. In units of trillion year 2005 USD and ppmv CO2:

GDP = 0.58 x CO2 - 174

An atmospheric chemist could easily obtain the size of the global economy within a 95% uncertainty bound of just 1.5%!

Of course, we have to be careful with correlation and causation. And even if the above relationship has worked extraordinarily well for the past 65 years, the underlying basis for a relationship between GDP and CO2 concentrations is in fact rather more complicated. Nonetheless, these data clearly support an argument that what matters for determining the concentrations of this key greenhouse gas are collective human activities.

A key point here is that this relationship is extremely tight and invariant over a very long time period during which the configuration of humanity has changed extraordinarily. There have been periodic wars, famines, and global economic crises. We do not consume the same raw materials with the same efficiencies to the same extent now as we did in the past. The mix of wind, solar, nuclear and fossil fuels has been consumed in widely varying mixtures using an extraordinary range of different technologies. Yet, despite all these changes, the relationship between our economic activities and CO2 seems to have remained invariant.

What is going on? Speculating, perhaps one way to look at it is to consider individually the impact of buying that fuel efficient Prius. A car that consumes less gas allows for an instantaneously incremental reduction in the demand for gas. Sounds great. Except, the oil resources for producing the gas are still available. If demand drops incrementally, then oil producers reduce prices to increase demand. Cheaper gas is more desirable, and so the collective response of all gas consumers is to consume more. Ultimately, the net effect on the collective rate of fossil fuel consumption of buying a fuel efficient Prius is zero (or even an increase).

“No man is an island entire of itself...” We have no individual carbon footprint. We are only “... a part of the main”. Only collectively can we reduce our impact on climate. As unpalatable as it may be, it seems the only successful climate action will be to dramatically and collectively deflate the global economy. Unfortunately, this may be a bit like asking that growing child, once it has reached a healthy adulthood, to voluntarily suffocate or shrink back to infancy.

Is there an alternative perspective that allows for change but is still consistent with the observations? It would be nice to think that our individual or collective actions can meaningfully decouple the economy from changes in atmospheric composition. But how?

Economics About Physics of the economy What is wealth?

Energy, Innovation and growth Economic inertia Economic Forecasting Jevons' Paradox

Physics vs Mainsteam Economics Is Macroeconomics a Science? The economic heat engine

Economics and Climate GDP is not Wealth Are renewables the answer?

Is population growth a problem? Will growth transition to collapse?

What is your carbon footprint? Media Publications Presentations FAQ Criticisms